From the origins to the 18th century. On foot and on horseback

From the beginning of time, every human group has sought to identify itself with a space. Whether it be in the valleys or on the plains, each community has developed an experience, a network of infrastructure and services in order to achieve a functional logic, quality of life, homogeneity and ensure its survival. As channels of exchange and communication, relations with neighbours have played a fundamental role in the construction and maintenance of these spaces.

Since time immemorial, the exchange of products and the communication of facts have been based on cries, words and a combination of symbols as different means of transmitting information as far as possible. This desire led the various peoples and civilizations, especially those in power, to organize systems for transmitting messages within the limits of their territories, systems that would be capable of improving the efficiency and speed of a simple market-day conversation.

The mail, as we know it today, was formed gradually over the centuries in a process that has evolved in a very uneven way, but which started in China between the 13th and 12th centuries BC. One of the highlights of this process was the system of communication by horse and chariot consolidated by the Romans, which was based on a network of roads and outposts, and which survived without any major modifications up to the end of the 18th century.

The ‘cursus publicus’

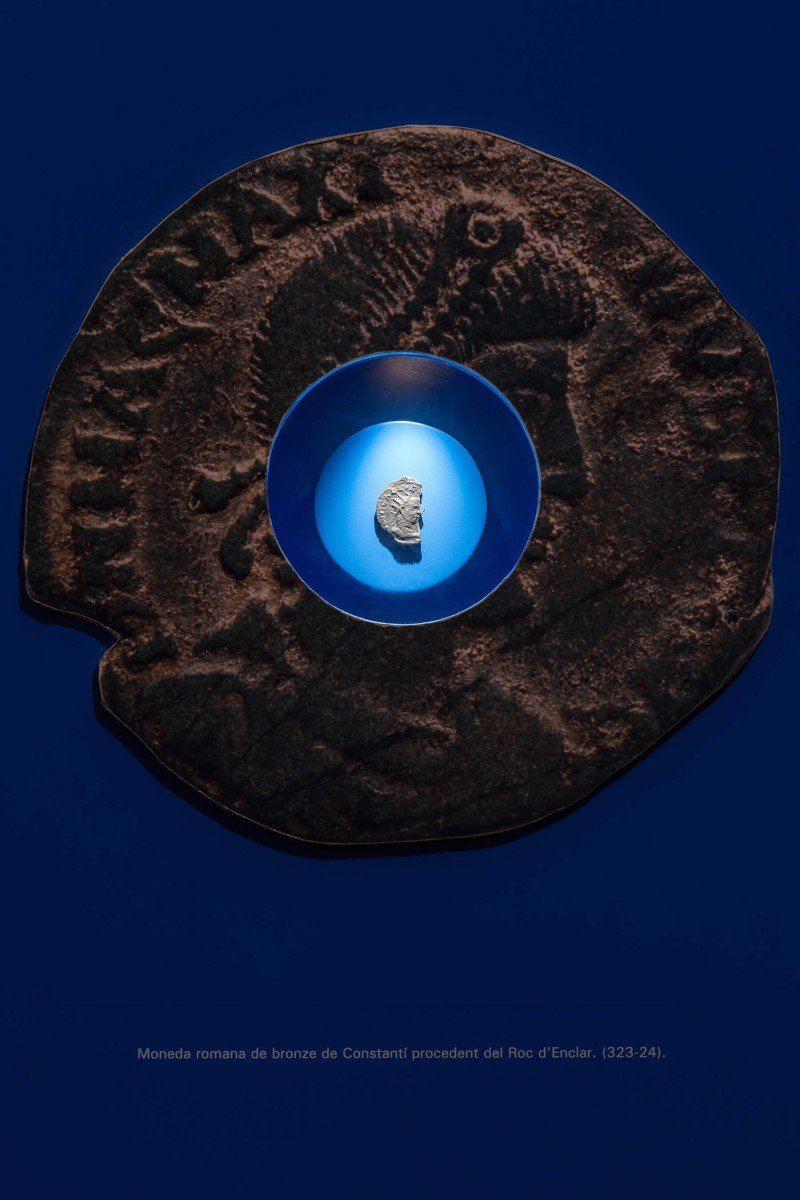

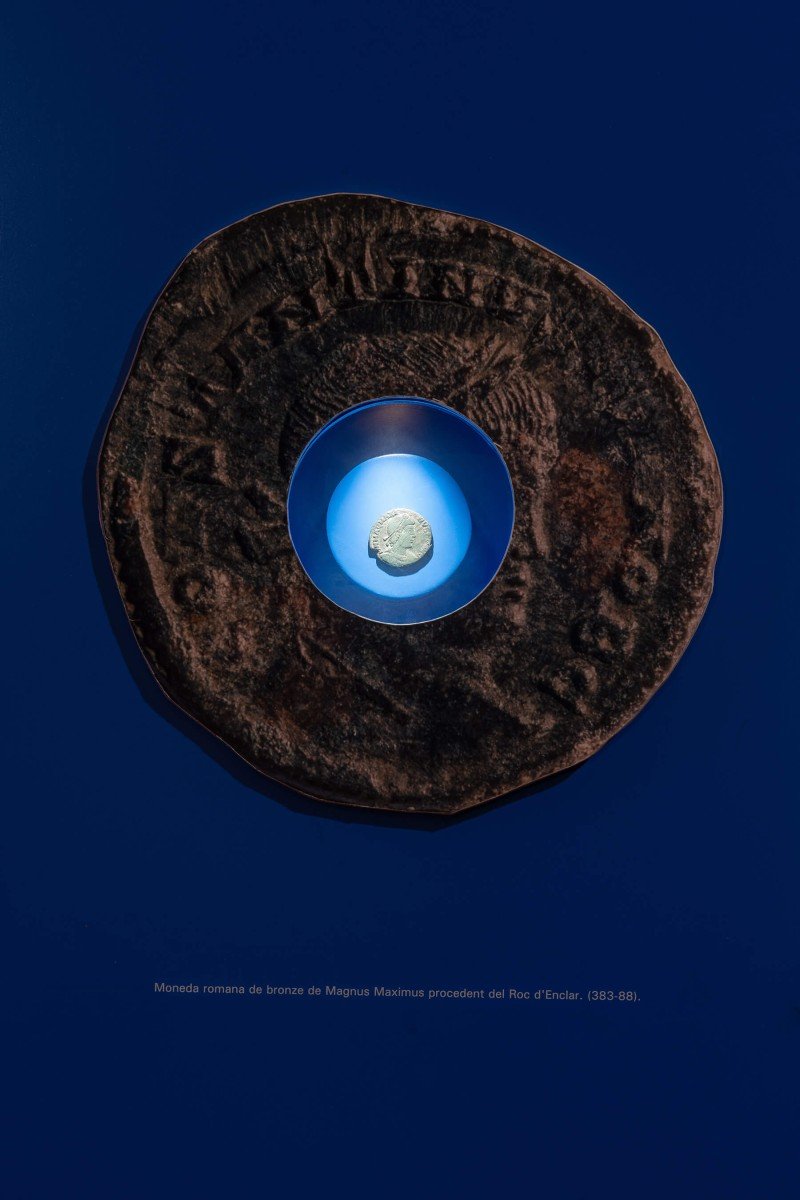

From the end of the 1st century BC, Rome came to manage, almost simultaneously, a territory that stretched from the Mediterranean to central Europe. Among all these lands, the Valley of Andorra was closely integrated with the rest as one of the secondary places of transit through the Pyrenees. Mail, both official and private, was one of the instruments that facilitated the exploitation, control and expansion of the Roman lifestyle to the more marginal areas. With the extensive road network, the emperor had a messenger service (cursus publicus) based on an infrastructure of outposts (mansions, taverns and inns) and on freedmen who were employed as couriers (cursioris ortabellarii) on horseback or in carriages. Large owners, on the other hand, used their own slaves to send letters to their families and friends.

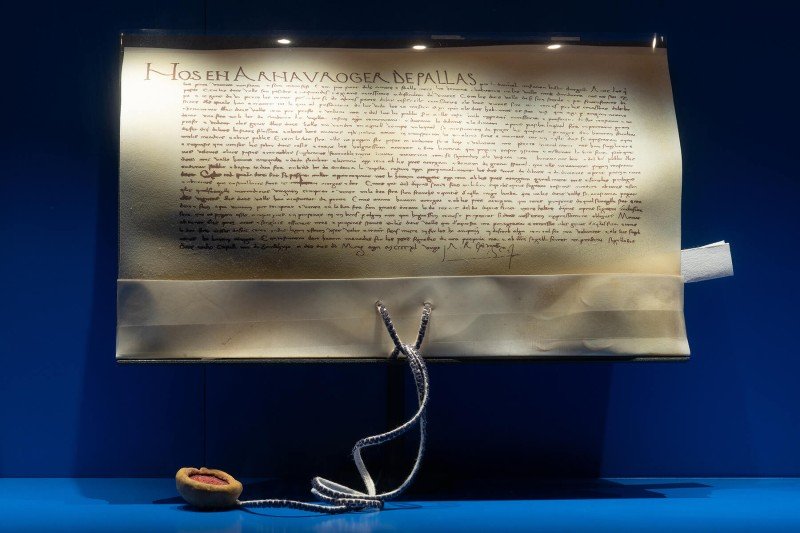

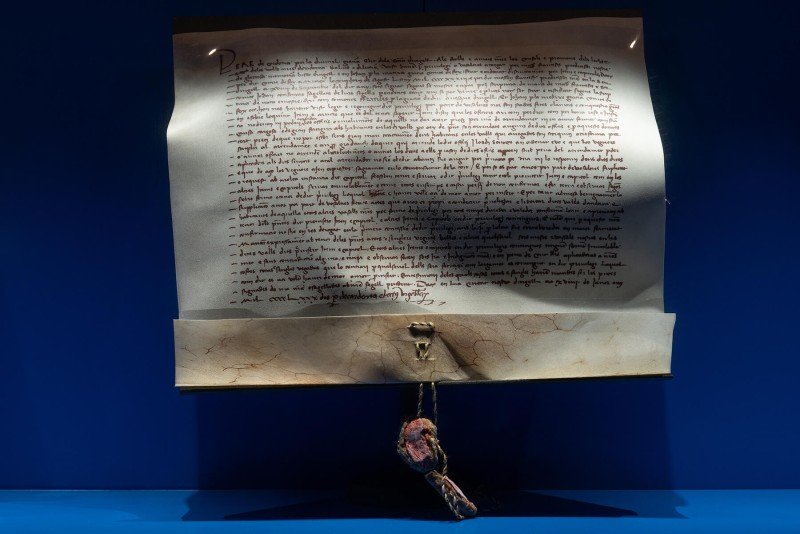

From the Middle Ages to the 16th century. The decline of the Roman infrastructure

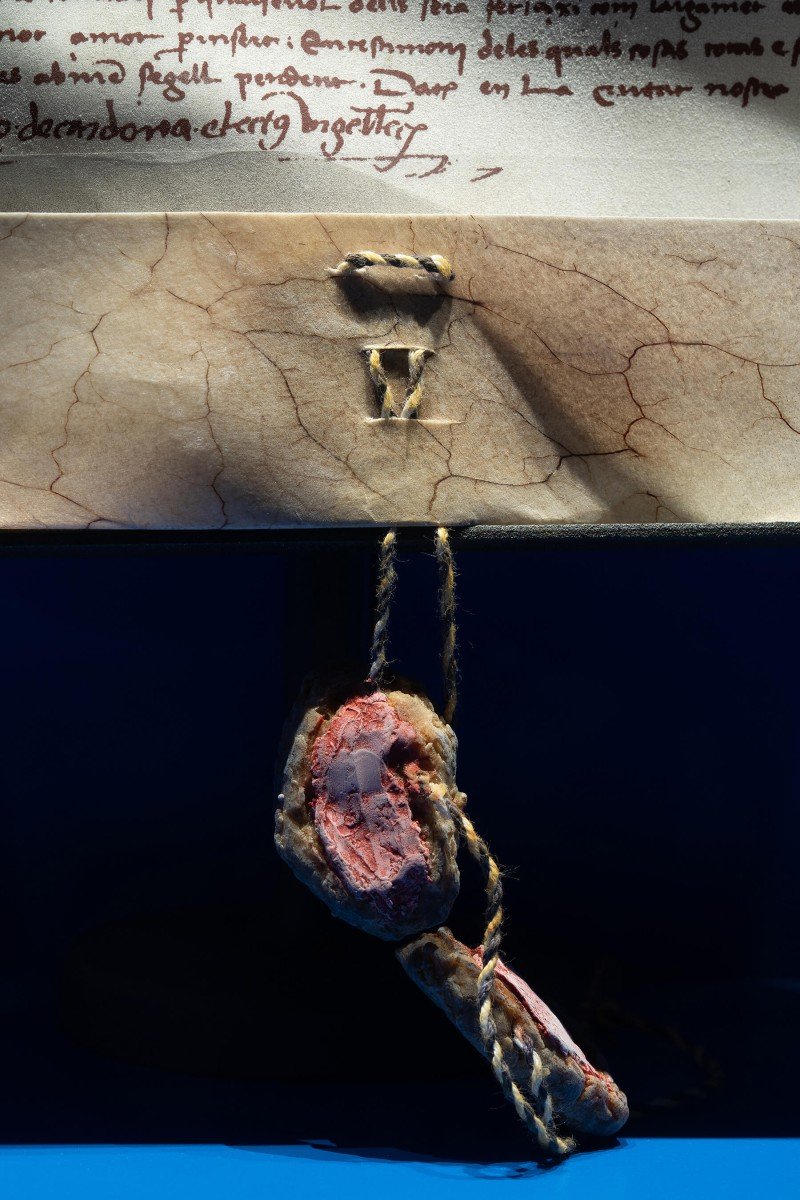

The Roman ways and roads remained in use without any major changes from the 8th to the 16th centuries. However, this road network was adapted to new requirements where exchanges and communications between neighbouring parishes or counties predominated. The mail, which continued to be linked to the aristocracy, ceased to be mostly long-distance and the outpost system was almost completely, though not totally, abandoned. The companies of couriers who initially were only at the service of nobles and later of merchants and city governments as well, distributed the documents, writs and notes on foot or on horseback.

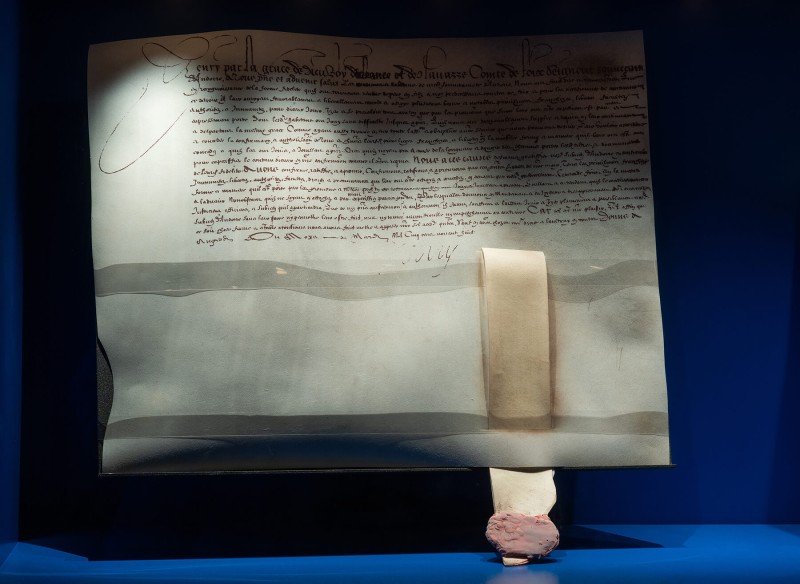

The 17th and 18th centuries. Post riders

Gradually, from the 16th century onwards, and especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, horse-drawn mail with post riders was reorganised once again in Western Europe. In France, for example, there were 252 stations in 1584, whereas by 1708 this number had increased to 800. Each had a determined number of horses according to the itinerary and the place. Once the animal was changed, the mail would continue and the postillion or mail carrier would follow it to the next stop and then send the horse back. The letters were sent without an envelope, folded and sealed with only the recipient’s name visible; it was only on rare occasions that any more precise information was added as the letters were not usually delivered directly.

.jpg)